by

Nick Zangwill

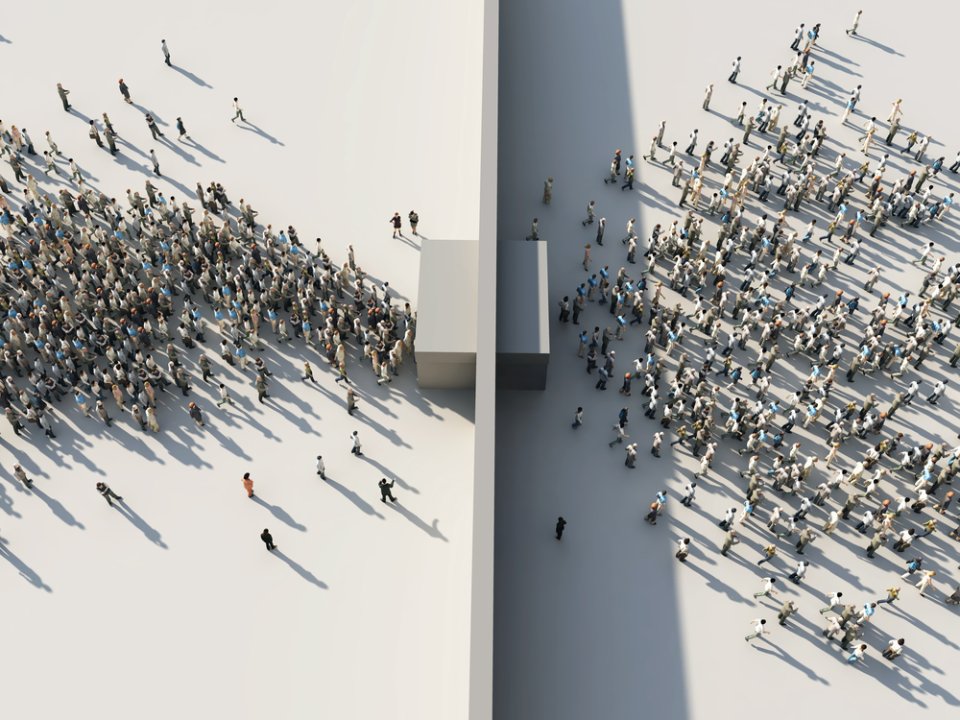

What do citizens of a country, within their gates, owe to foreigners, outside the gates, who wish to enter on account of their needs? The answer is simple: nothing. Furthermore, this negative answer is obvious, although it is perhaps not obvious that it is obvious. To see why it is obvious, we need to make three distinctions.

The most important distinction is between rights and goods. People possess rights, and there are things that are good for them. Each of these—rights and goods—allows further distinctions. Within the realm of rights, we may distinguish negative rights, which require non-interference by others, and positive rights, which require others to provide assistance. And within goodness, we may distinguish impartial from good only in relation to specific individuals or restricted groups. For instance, something might be impartially good, or "good for my family," "good for my country," or "good for my culture." That makes three distinctions. While these distinctions are somewhat crude and no doubt require further elaboration, they are nevertheless, important; and applying them to the issue of immigration enables a significant reorientation and expansion of the political options. Not only does it allow more conservative views to be articulated, it also reveals the underlying concerns that should underpin debates over more or less liberal immigration policies.

Let us now consider the distinction between positive and negative rights. There are certain rights that all human beings possess by virtue of their universal nature. Following Isaiah Berlin we might call these negative rights. These rights stem from our nature as self-determining, free beings who do things for reasons. Because of this nature, others cannot interfere with us, toy with us, or use us merely as a means to an end. For example, if I am trying to raise my right arm, I have a negative right that others should not prevent me from doing so, assuming no other relevant factors are in play. This means others must leave me alone to live my life as I see fit, unless my actions infringe upon the rights of others.

A positive right is something altogether different. It places a demand on others to act in ways that assist me if I am in need or facing trouble. If I have a positive right, then others are obliged to help me. This is not about non-interference; it requires action. They must get up from their seats and do something that will benefit me. A distinction between negative and positive rights is fundamental, and no one has cast serious doubt on it.

What, then, about those foreigners outside the gates who wish to enter to become citizens? What about asylum seekers and those who want to be immigrants? Many have argued that asylum seekers, and aspiring immigrants, have a right to enter countries because of their needs. This claim should be resisted, however, and the above distinctions make it obvious why. All human beings, including those outside the gates, have negative rights. As such, we citizens, inside the gates, cannot treat those outside merely as means to an end. We cannot exploit them, enslave them or wage war against them except in self-defence. Their negative rights mean they must be respected as human beings. However, they lack positive rights that

mean that we must come to their aid simply because they have needs or because they would benefit from becoming citizens of our country. They have negative rights, but no positive rights. That means that citizens owe them nothing.

An exceptional case might be when outsiders have served the nation in some way. Gurkhas in the British army might be an example. In such cases, those inside might owe those outside something, which may or may not be citizenship. But without something of that sort they are owed nothing. The mere fact that there is inequality of wealth or of some other good between nations is certainly not such a special reason.

Is this heartless? Not at all. Recall the other moral concept: the good. We might feel compassion and take account of the good of outsiders. We might think we should help them because of their needs and our ability to benefit them. Perhaps. But this has nothing to do with rights. Nothing. Rights serve a fundamentally different role in our moral and political thinking, and the issue cannot be discussed meaningfully without acknowledging this distinction. Reducing all moral or political matters to questions of rights, or even undiscriminating obligations, for instance, flattens the moral and political landscape in a disastrous way.

Rights, and in particular positive rights, should not be allowed to become a kind of legal battering ram to break down the gates and allow outsiders to storm into a nation. Such is the notion of rights deployed by many in the ‘human rights’ industry. Rights of this kind are like multiplying zombies that are a mortal threat to almost everything of value, and in particular to the blessings of nationhood.

Once rights are put to one side, there can be a serious discussion about how to weigh the good of citizens against the good of foreigners, and about various aspects of the good in the near and far future. It is overwhelming plausible that we may weigh the good of citizens more than that of foreigners, just as we may weigh the good of family more than that of non-family. Whether or not those outside the gates should be allowed to enter and become citizens depends primarily on considerations of the good of the nation and its members—both as they currently exist and as they will become—along with the degree of compassion deemed appropriate for the good of those aspiring immigrants who are not blessed to be part of the nation. But citizens do not owe foreigners help just on account of their good. Rights have nothing to do with it.

The full text can be downloaded here.

© 2025 INIR. All rights reserved.

The article reflects the author’s personal views.

INIR does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of INIR, its staff, or its trustees.