by

Nayla Rush

As soon as he took office, President Trump suspended[1] the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) with an executive order titled “Realigning the United States Refugee Admissions Program”[2]. USRAP was created following the Refugee Act of 1980 to provide a uniform procedure for refugee admissions and to authorize federal assistance to resettled refugees (and other eligible populations such as those holding Special Immigrant Visas[3]) after arrival in the United States. The aim was to end an ad hoc approach to refugee admissions that had characterized U.S. refugee policy since World War II.

Many U.S. activists and lawmakers from both parties, were quick to criticize Trump’s USRAP pause and its repercussion for certain Afghan nationals who were hoping to come here. Rep. Scott Peters (D-Calif.) claimed the pause resulted in “abandoning our Afghan allies”,[4] while Rep. Michael Mc Caul (R-Texas) urged Trump to make an exception and “admit Afghan allies” during this refugee freeze.[5] Shawn VanDiver, president of AfghanEvac (the leading coalition of groups advocating for the admission of Afghans and a “pathway to permanent residency” for Afghan evacuees), criticized Trump for leaving “our Afghan allies” to die.[6]

Trump’s suspension of the refugee resettlement program has since been blocked by a judge.[7] As things unfold in court and we monitor future Afghan arrivals, it is important to clarify matters upfront. Indeed, there is a confusion as to which Afghan nationals the United States has been welcoming ever since its troops left Afghanistan in the summer of 2021.

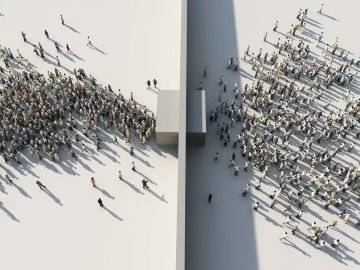

Who exactly is the United States welcoming and why? Are they “allies” (Afghans who helped U.S. troops there), or refugees (those who fear persecution from the Taliban), or migrants (those who simply want to come here)?

These questions are important because, with every answer, comes a specific admission status: Afghan “allies” are eligible to Special Immigrant Visas (SIVs), “persecuted” Afghan can be admitted as refugees under the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP), and Afghan migrants are “paroled” in.[8] Both SIVs and refugees are authorized to live permanently in the United States (SIVs are granted green cards upon admission, refugees, one year later), while parolees are supposed to be here temporarily.

Contrary to sensational claims, most of the Afghans the United States has been (and might continue) welcoming are not U.S. “allies” nor are they “refugees” in need of resettlement.[9] Which means, the U.S. government, in general, is not “saving the lives” of Afghans, nor is it “leaving them to die”. It is mainly opening the door (with a “parole” card) to those who wish to come here, whether to join family members/friends or just have a shot at a better life in the United States.

Over 200,000 Afghan newcomers were welcomed into the United States under the Biden-Harris administration following the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan in 2021. They were, for the most part, granted parole.

From October 2021 through end of December 2024, only 28,145 Afghans[10] were admitted here as refugees through USRAP and only 17,000 SIVs were given to principal applicant Afghan allies (in total 68,654 Afghan[11] principal applicants and family members were granted SIVs – eligible family members are spouses and children of any age, whether married or unmarried and make up usually[12] at least four times that of principal applicants).

SIVs are numerically capped. As of January 1st, 2025, only around 10,000 SIV spots were available to principal applicants.[13]

Vetting

We can’t talk about the admission of Afghan nationals without addressing the problem of efficient vetting. Some claim that Afghans are rigorously vetted,[14] but, as my colleague Andrew Arthur has explained, the screening and vetting process of Afghan evacuees is far from rigorous.[15] We know of the absence of dependable screening measures for nationals from conflict zones, such as Afghans and Syrians, and of the impossible task of crosschecking backgrounds.[16]

Furthermore, while vetting is essential, shared values and successful integration are the best shields against radicalization. A young Afghan (21 at the time) who was evacuated in 2021 was arrested less than two months into his stay in the United States for engaging in a prohibited sexual conduct with a minor and possessing child pornography images. Most of the mitigating circumstances presented by the defense to get leniency at sentencing touched on his cultural difference: some sexual conduct that is deemed criminal in the United States is considered normal in Afghanistan.[17] Even if he was indeed “rigorously screened” and all the documents pertaining to his judicial history in Afghanistan were available, he would still have been cleared to enter the United States. In this young man’s case, nothing was missed because there was probably nothing to find. His village in rural Afghanistan does not have a regularized criminal justice system; disputes there are resolved through inter-family mediation. It is a fact that newcomers do not necessarily leave their beliefs and biases behind.[18]

“Allies”

“Allies” are those who worked as translators, interpreters, or other professionals employed by or on behalf of the U.S. government in Afghanistan who face a serious threat as a result of that employment. They have access to Special Immigrant Visas (SIVs) to come to the United States.[19] Upon admission, SIV holders are granted Lawful Permanent Residence (LPR), also known as green cards.[20] They receive the same benefits and federal services as refugees under the USRAP.

SIV spots are numerically limited.

SIVs for Afghans. There are two SIV programs designed for certain Afghan nationals.

The first is a permanent program. The “Special Immigrant Visas (SIVs) for Afghan Translators/Interpreters” offers visas to up to 50 persons a year (the cap excludes family members such as spouses and children).[21]

The second is temporary. The Special Immigrant Visas program for Afghans who were employed by or on behalf of the U.S. government[22] was capped at 1,500 principal applicants per year for FY 2009 through FY 2013. Any unused numbers could be carried forward from one fiscal year to the next. Congress kept adding to these numbers throughout the years. It is estimated there are less than 10,000 SIVs for principal applicants remaining.[23] If Congress doesn’t authorize additional ones, the Afghan SIV program is set to run out of visas.

Refugees

Refugees are those who are “unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.”[24] Refugees are resettled into the United States through the USRAP and must apply for a green card one year after arrival. Refugees, like SIVs, have access to the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) assistance and federal benefits.

Refugee spots fall under a ceiling and follow regional allocations set by the U.S. president every fiscal year. FY 2025 refugee ceiling was set at 125,000 by President Biden, with a regional allocation for Near East/South Asia fixed at 30,000-45,000.

Priority 2 and Priority 1 Refugee Access to Afghans. In August, 2021, the Biden-Harris administration announced a Pre-defined Group Access P-2 (Priority 2- Group Referrals) to USRAP for certain Afghan nationals and their eligible family members.[25] Pre-defined Group Access Priority 2 is available to Afghans who are not SIVs or SIV applicants but work/ed for a project in Afghanistan supported by a U.S. government grant or cooperative agreement or to those who work/ed for a U.S.-based media or NGO as a freelancer.[26]

Afghans who work/worked for sub-contractors and sub-grantees do not qualify for the P-2 designation but can qualify for P-1 referrals. The Department of State under the Biden-Harris administration designated certain NGOs that assist refugees to make P-1 referrals through the Equitable Resettlement Access Consortium (ERAC) led by HIAS, RefugePoint, and the International Refugee Assistance Project (IRAP).[27] HIAS and IRAP joined with other advocates to sue President Trump for suspending USRAP.[28]

There are millions of Afghans who did not assist U.S. forces, but who could nonetheless end up wanting to leave their country as refugees, fearful of a Taliban rule. How many should the United States welcome? Thousands, millions?

Migrants/Parolees

Migrants are those who are not SIV or refugee status holders but are granted “parole” to be able to enter or stay in the United States.

The parole provision in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) gives the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) discretionary authority to parole aliens into the United States temporarily and “only on a case-by-case basis for urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit”.[29] Parolees can stay in the United States for the duration of the grant of parole (typically one year, two for Afghans as requested by former DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas).[30] They can also apply for re-parole.[31]

Contrary to SIVs and refugees, parolees are not provided with a pathway to citizenship and are expected to leave when their period of parole expires. Parolees can apply for work authorization but are not eligible for ORR’s assistance. This changed under the Biden-Harris administration for Afghan parolees who were provided with employment authorization incident to parole.[32] Afghan parolees were also made eligible for the same resettlement assistance, entitlement programs, and other federal benefits as refugees and SIVs. Moreover, in 2022, ORR, under the Biden-Harris administration, awarded $35 million to the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (USCRI) to provide free and direct legal services to Afghan parolees.[33]

There is no numerical limit to parolees.

Most Who Came and Want to Come Are Not “Allies”

Despite the ongoing narrative, most of the Afghans who were evacuated during “Operation Allies Welcome”[34] (July-August 2021) following the withdrawal of U.S. troops were not “allies” who risked their lives to help U.S. forces in Afghanistan.[35] Nor were the evacuees formally granted refugee status; hence, the use of parole as the entry ticket to the United States.

But efforts to admit Afghans did not stop with the 2021 evacuation process. The Biden-Harris administration renamed “Operation Allies Welcome” as “Enduring Welcome” to bring certain family members who remained abroad.[36] Moreover, Afghan parolees were able to sponsor more Afghans to follow them here under parole. The Biden-Harris administration also launched the “Sponsor Circle Program for Afghans” to encourage U.S.-based supporters (including parolees and other newcomers with “temporary authorization” to remain in the United States), to sponsor other Afghans (who were then allowed in under parole).[37]

Re-parole was made available to certain Afghan parolees in 2023.[38] As we wait for the outcome of the ongoing court battles on all these programs, we also wonder about the fate of the thousands of Afghan parolees when their parole or re-parole ends soon (in 2025 for many of them). Will they be asked to leave the country? And if they don’t, will the Trump administration move to deport them?

[1] Nayla Rush, “Trump Suspends Refugee Admissions”, CIS, January 24, 2025, https://cis.org/Rush/Trump-Suspends-Refugee-Admissions.

[2] The White House, January 20, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/realigning-the-united-states-refugee-admissions-program/.

[3] “Iraqi and Afghan Special Immigrant Visa Programs”, Congress.gov, January 15, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R43725.

[4] Rep. Scott Peters, post on X, February 9, 2025, https://x.com/RepScottPeters/status/1888418321567285597.

[5] Mandy Taheri, “Republican Urges Trump Admin to Admit Afghan Allies During Refugee Freeze”, Newsweek, February 9, 2025, https://www.newsweek.com/republican-urges-trump-admin-admit-afghan-allies-during-refugee-freeze-2028462?utm_term=Autofeed&utm_medium=Social&utm_source=Twitter#Echobox=1739126067.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Advocates react to judge granting preliminary injunction in Trump refugee ban challenge”, IRAP, February 25, 2025, https://refugeerights.org/news-resources/advocates-react-to-judge-granting-preliminary-injunction-in-trump-refugee-ban-challenge.

[8] “Immigration parole”, Congressional Research Service, October 15, 2025, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/homesec/R46570.pdf.

[9] UNHCR, “Projected Global Resettlement Needs 2024”, June 26, 2023, https://reliefweb.int/report/world/unhcr-projected-global-resettlement-needs-2024-enar?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQjw0Oq2BhCCARIsAA5hubXWLtviLbJY-fAfzHoMtx8JrldOSs4CBOBeYP27p53ypm7hQsT8Z0IaAmhlEALw_wcB.

[10] Refugee Processing Center, “Admissions and Arrivals”, https://www.wrapsnet.org/admissions-and-arrivals/.

[11] Ibid.

[12] U.S. Department of State, “Report to Congress on Posting of the Afghan Special Immigrant Visa Quarterly Report on the Department of State’s Website Section 1219 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2014 (Pub. L. No. 113-66)”, 2024, https://travel.state.gov/content/dam/visas/SIVs/Afghan-Public-Quarterly-report-Q4-October-2024.pdf.

[13] Global Refuge, “The Afghan Special Immigrant Visa Program”, February 4, 2025, https://www.globalrefuge.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/SIV-FAQ-1.pdf.

[14] Shawn J. VanDiver, “Letter to Secretaries Rubio, Hegseth, and Noem”, AfghanEvac, February 8, 2025, https://afghanevac.org/letter.

[15] Andrew R. Arthur, “DoD Watchdog Issues Chilling Indictment of Afghan Vetting”, CIS, February 28, 2022, https://cis.org/Arthur/DoD-Watchdog-Issues-Chilling-Indictment-Afghan-Vetting.

[16] Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs full committee hearing “Threats to the Homeland”, October 8, 2015, https://www.hsgac.senate.gov/hearings/threats-to-the-homeland2015/.

[17] Nayla Rush, “Is Cultural Leniency in Order for Afghan Sexual Offenders?”, CIS, September 20, 2023, https://cis.org/Rush/Cultural-Leniency-Order-Afghan-Sexual-Offenders.

[18] Nayla Rush, “Resettled Refugees Do Not Necessarily Leave Their Beliefs and Biases Behind”, CIS, November 6, 2023, https://cis.org/Rush/Resettled-Refugees-Do-Not-Necessarily-Leave-Their-Beliefs-and-Biases-Behind.

[19] U.S. Department of State, “Special Immigrant Visas (SIVs) for Iraqi and Afghan Translators/Interpreters”, https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/us-visas/immigrate/siv-iraqi-afghan-translators-interpreters.html.

[20] “Iraqi and Afghan Special Immigrant Visa Programs”, Congress.gov, January 15, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R43725.

[21] U.S. Department of State, “Special Immigrant Visas (SIVs) for Iraqi and Afghan Translators/Interpreters”, https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/us-visas/immigrate/siv-iraqi-afghan-translators-interpreters.html.

[22] U.S. Department of State, “Special Immigrant Visas for Afghans – Who Were Employed by/on Behalf of the U.S. Government”, https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/us-visas/immigrate/special-immg-visa-afghans-employed-us-gov.html.

[23] Global Refuge, “The Afghan Special Immigrant Visa Program”, February 4, 2025, https://www.globalrefuge.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/SIV-FAQ-1.pdf.

[24] UNHCR, “What Is a Refugee?”, https://www.unhcr.org/us/what-refugee#:~:text=The%201951%20Refugee%20Convention%20is,group%2C%20or%20political%20opinion.%E2%80%9D.

[25] U.S. Embassy in Kabul, “U.S. Refugee Admissions Program Priority 2 Designation for Afghan Nationals”, August 2, 2021, https://af.usembassy.gov/u-s-refugee-admissions-program-priority-2-designation-for-afghan-nationals/.

[26] “Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2025”, Report to the Congress, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Report-Proposed-Refugee-Admissions-for-FY25.pdf.

[27] https://hias.org/, https://www.refugepoint.org/, https://refugeerights.org/news-resources/legal-resources-for-afghans.

[28] IRAP, “Pacito v. Trump: Challenging Trump’s suspension of USRAP”, https://refugeerights.org/news-resources/pacito-v-trump-challenging-trumps-suspension-of-usrap.

[29] “Immigration Parole”, FAS Project on Government Secrecy, October 15, 2020, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/homesec/R46570.pdf.

[30] Geneva Sands, “DHS allows Afghans temporary entry into US under immigration law”, CNN, August 27, 2021, https://edition.cnn.com/2021/08/27/politics/dhs-afghans-temporary-entry-parole/index.html.

[31] “Afghan Re-Parole FAQs”, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/information-for-afghan-nationals/re-parole-process-for-certain-afghans/afghan-re-parole-faqs.

[32] “Certain Afghan Parolees Are Employment Authorized Incident to Parole”, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, August 6, 2023, https://www.uscis.gov/newsroom/alerts/certain-afghan-parolees-are-employment-authorized-incident-to-parole.

[33] “Immigration Legal Services for Afghan Arrivals”, Administration for Children and Families, January 19, 2023, https://acf.gov/sites/default/files/documents/orr/DCL-23-15-Immigration-Legal-Services-for-Afghan-Arrivals.pdf.

[34] Department of Homeland Security, “Operation Allies Welcome”, January 22, 2025, https://www.dhs.gov/archive/operation-allies-welcome.

[35] Nayla Rush, “Operation Allies Refuge: Who Exactly Was on Those Planes?”, CIS, September 14, 2021, https://cis.org/Rush/Operation-Allies-Refuge-Who-Exactly-Was-Those-Planes.

[36] “Enduring Welcome Program”, Military One Source, https://www.militaryonesource.mil/benefits/enduring-welcome-program/.

[37] “Sponsor Circle Program”, Sponsor Circles, https://www.sponsorcircles.org/about.

[38] “USCRI Statement on Launch of New Re-parole Process for Afghans”, U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, June 9, 2023, https://refugees.org/uscri-statement-on-launch-of-new-re-parole-process-for-afghans/.

The full text can be downloaded here