by

Nicolas Pouvreau-Monti

“There is always the feeling that borders are sieves, that migratory flows are not under control. So we are going to bring them under control with concrete measures.” In his first interview after his appointment to the office of Prime Minister in France, Michel Barnier sought to set a clear course for the immigration policy of his new government. The nomination of Bruno Retailleau as Minister of the Interior has marked another signal in a more ‘restrictive’ direction.

Of all the questions associated with this issue, which has become a major one for French society, that of its economic and budgetary impact is certainly one of the most hotly debated. While opinion polls show that the vast majority of the public would like to see a reduction in migratory flows, our compatriots are more divided on this specific aspect of the subject: 38% of French people believe that ‘immigration brings more financially to France than it costs’, according to an Ifop-Fiducial study published last year[i].

In this respect, valuable databases have been made public by the OECD[ii], as part of its most recent publication on ‘Indicators of immigrant integration’. A comparative analysis of these data reveals a striking fact: on the whole, immigrants to France are less integrated into the labor market and poorer off than elsewhere in Europe. The employment rate of people born abroad is one of the lowest in France among all EU countries: only 61% of them were in work in their 15 to 64 age group in 2021, 7 points lower than the native-born population.

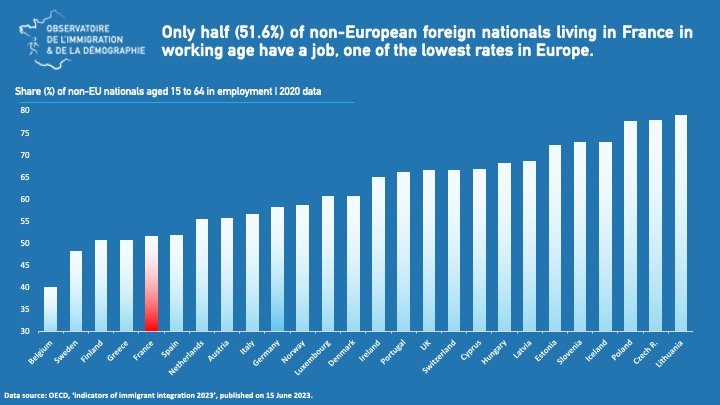

An analysis based on nationality rather than place of birth reveals even more striking findings: only half (51.7%) of non-European foreigners of working age had a job in France in 2020, a rate 14 points lower than that of French citizens – but also 15 points lower than non-European foreigners in the UK, 9 points lower than in Denmark, and 6 points lower than in Germany.

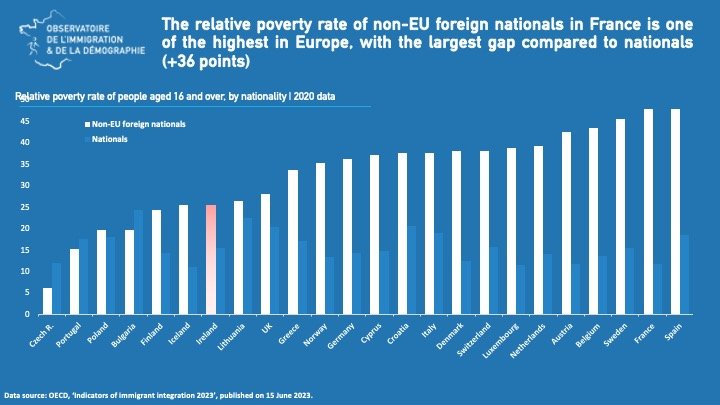

Another angle can be to look at the activity rate: ‘active’ people – those in work or looking for work – accounted for only 64% of non-European foreigners of working age, the third lowest rate in the whole of the EU (followed only by Belgium and the Netherlands). The unemployment rate for non-European foreigners in France was more than double of that of the French: 19.5% compared with 8%. Not unrelated to the above data, the relative poverty rate (calculated in relation to the median wage in each country) of non-European nationals living in France is the highest in Europe, on a par with Spain: 47.6% of them were living below the poverty line in 2020, a proportion four times higher than that of French citizens (11.5%) with a gap of 36 points between them – a record gap in the zone.

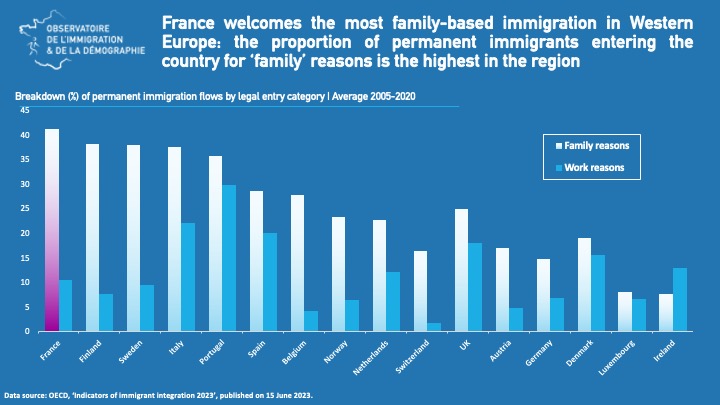

To better understand these striking findings, several points need to be considered. The first is the breakdown of legal reasons for settling in France: the proportion of immigrants (of all origins) entering the country for ‘family’ reasons is the highest in France as compared to all Western Europe. It accounted for 41.2% of permanent immigrant entries over the period 2005-2020, a rate three times higher than in Germany, compared with 10.5% for ‘work’ reasons.

The second key to understanding the situation lies in the high prevalence of immigrant profiles with a ‘low’ level of education, according to the classification used by the OECD: in 2020, 33% of foreign-born people aged between 15 and 64, living in France and having left the education system, had only a level of qualification lower than or equal to the brevet des collèges[iii], a rate twice as high as that of people born in France (16%). If we focus on nationality, this asymmetry is even more striking: 42.6% of non-European foreigners in the same age groups had no qualifications at all, or only the brevet level, a proportion 26 points higher than that of the French (16.7%).

A third factor could be a greater cultural ‘distance’ from the host society, linked to the origins of the flows received in our country. France has the most African immigration of all developed countries, with a very marked difference compared to our neighbors: 61% of immigrants aged between 15 and 64 living in France in 2020 were from Africa (Maghreb and non-Maghreb), three times the EU average. In Portugal, which has the second highest proportion of African immigrants after France, the proportion was only 35% – 26 percentage points lower than in France.

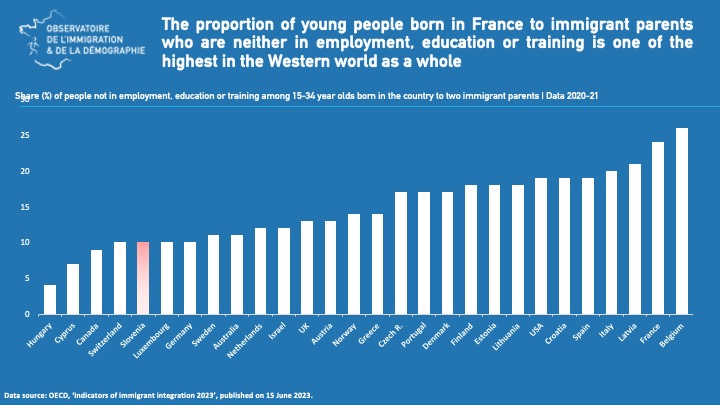

The particular structure of immigration in France is reflected in the different fertility rates on French soil, which reflect the habits at work in the countries of origin. In 2019, women born outside the European Union and living in France had an average of 3.27 children in their lifetime: this was the highest fertility rate in Western Europe, and twice as high as that of women born in France (1.66). However, the difficulties faced by the ‘second generation’ of immigrants appear to be more marked in France than elsewhere: the proportion of young people born in France to immigrant parents who are neither in employment, education or training (24%) is the second highest in Europe – and even in the Western world. Only Belgium has worse figures in this field.

Taken together, these data point to a clear diagnosis: that of the concerning economic, budgetary, and social results of the immigration policy pursued in the country, now for several decades. While there have been many individual success-stories as a result of this immigration, and a differentiated approach needs to be adopted according to geographical origins (depending on which integration trajectories vary considerably), the fact remains that rational analysis reveals a reality marked by a high prevalence of ‘net tax consumer’ profiles, over-beneficiaries and under-contributors of collective solidarity schemes. These profiles are not limited to the unemployed and the economically inactive: an immigrant or foreigner working in a low-skilled – and low-paid – job is likely to consume more public spending than he or she contributes.

In order to restore balances in this area, it would finally be important to consider immigration like any other public policy, with the aim of minimizing the costs and maximizing the benefits for French society. The task of initiating this Copernican revolution now falls to Michel Barnier’s government.

[i] IFOP-Fiducial, « Le regard des Français sur l’immigration », 16/06/2023: https://www.ifop.com/publication/le-regard-des-francais-sur-limmigration-3/.

[ii] OECD, «Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2023», 15/06/2023: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2023/06/indicators-of-immigrant-integration-2023_70d202c4.html.

[iii] A lower secondary education diploma that is usually awarded to youngsters aged 14-15.

You can download the full text here

© 2024 INIR. All rights reserved.

The article reflects the author’s personal views.

INIR does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of INIR, its staff, or its trustees.