by

Jason Richwine

August 14, 2024

In the decades following the American Civil War, millions of white Southerners moved away from the old Confederacy and settled in other parts of the United States, especially the border states and the West. These migrants made a lasting cultural impression. In fact, research shows that the greater the percentage of white Southern migrants in a non-Southern U.S. county in 1940, the more likely that county is today to oppose abortion, build evangelical churches, listen to country music, and even favor barbecue chicken over pizza.[i]

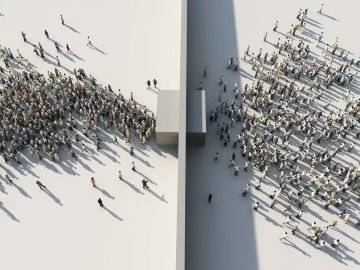

Clearly, Southern migrants were not assimilated into the pre-existing cultures of their new homes outside the South. Instead, they transplanted their own culture, sharing it with non-Southern neighbors and transmitting it to the next generation. For analysts of immigration, a natural question arises: If culture persists among domestic groups as they move around within the same country, isn’t it likely that culture will also persist among immigrants who move to new countries from abroad?

The answer is yes. Contrary to the promises of immigration advocacy groups, immigrants and their descendants do not completely assimilate to the cultures of their new countries, nor do they blend into an undifferentiated “melting pot.” Decades of empirical evidence instead demonstrate the persistence of ancestral culture, affecting fundamental values and behaviors such as trust, civic engagement, savings, and even political views.

In an American context, one of the most famous histories of cultural persistence is Albion’s Seed, which chronicles how four groups of British settlers in North America established distinctive cultures that persist in some form to the present day.[ii] The author, David Hackett Fischer, contrasts Puritans in New England, Quakers in the mid-Atlantic region, distressed Cavaliers in the upper South, and “Scotch-Irish” borderers in Appalachia. Fischer describes how these groups had different conceptions of order, power, and freedom that shaped their approaches to education, civics, trust, crime, and government structure. He then shows that the regions of the U.S. in which each group settled still exhibit these cultural differences today.

Cultural persistence is not limited to America’s founding peoples. In a classic study for the Journal of Politics, political scientists Tom Rice and Jan Feldman argue that later immigrant groups brought their own civic values that are still detectable in their descendants more than 100 years later.[iii] The study’s authors first created an index of civic culture – based on questions related to social trust, tolerance, and community engagement – and then measured the strength of civic culture in both Europe and the U.S.

What emerged was a strong and positive correlation between European American groups and their ancestral countries. Put more concretely, in Europe, Denmark has a more civic culture than Britain, which in turn has a more civic culture than Italy. In the U.S., the same order emerges – Danish Americans are more civic than British Americans, who are more civic than Italian Americans. There should be no such relationship if the U.S. were truly a “melting pot” where distinctive cultures disappear.

Much of the cultural persistence literature focuses on the U.S., but there is little indication that immigrant assimilation is more complete elsewhere. In fact, the U.S has historically prided itself on integrating its Great Wave of immigrants from 1880-1920 with the old-stock Americans who came before. The country adopted a “nation of immigrants” ethos and considered itself especially good – perhaps uniquely good – at welcoming newcomers. And yet, despite all of the surface success, social scientists can still detect in the data persistent cultural differences – even among the groups that most people describe today as simply “white Americans.”

Given the limits of the melting pot in the U.S., consider the assimilation challenges that Europe faces. While the U.S. has hundreds of years of experience with mass migrations, most European countries have mere decades. In addition, many of the immigrants Europe receives today come from the Islamic world, a place that is culturally far different from any of the countries which sent large numbers of immigrants to the U.S. in the past. The idea that European countries will absorb these waves of immigrants without experiencing significant cultural changes is implausible.

What might the practical impact of those changes be? The economist Garett Jones, author of The Culture Transplant, worries first about the effect on productivity.[iv] Since a nation’s culture undergirds its wealth-creating institutions, the danger he sees for high-income countries is that mass immigration could result in the importation of cultures that are not conducive to prosperity. He particularly worries that innovation could suffer in a less supportive environment.

The impacts go beyond economics, however. The studies discussed above focus on civic engagement, trust, and other components of social capital. “Where levels of social capital are higher, children grow up healthier, safer and better educated; people live longer, happier lives; and democracy and the economy work better,” explains political scientist Robert Putnam.[v] If immigrants lower social capital in their new countries, all of those quality-of-life indicators could be affected.

Thinking about specific impacts leads to a broader point: Immigration brings changes that cannot be undone. Taxes go up and down, regulations come and go, but the consequences of immigration will extend beyond our lifetimes.

[i] Samuel Bazzi, Andreas Ferrara, Martin Fiszbein, Thomas Pearson, and Patrick A Testa, "The Other Great Migration: Southern Whites and the New Right", The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 138 (2023), pp. 1577-1647. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjad014

[ii] David Hackett Fischer, Albion's Seed : Four British Folkways in America, New York: Oxford University Press, 1989. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/999613769502121

[iii] Tom W. Rice and Jan L. Feldman, "Civic Culture and Democracy from Europe to America", The Journal of Politics, Vol. 59 (1997), pp. 1143-1172. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2998596

[iv] Garett Jones, The Culture Transplant: How Migrants Make the Economies They Move to a Lot Like the Ones They Left, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2022. http://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=35594

[v] Robert D. Putnam, "E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty-First Century", Scandinavian Political Studies, Vol. 30 (2007), pp. 137-174. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2007.00176.x

You can download the full text here

© 2024 INIR. All rights reserved.

The article reflects the author’s personal views.

INIR does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of INIR, its staff, or its trustees.